Seconda parte.

Il Mausoleo di Adriano aveva la forma di un grande torrione circolare e per questo motivo fu trasformato in fortezza, analogamente a quanto avvenne con il Mausoleo di Cecilia Metella sull'Appia antica, che venne incluso nelle fortificazioni del Castrum Caetani.

Il Mausoleo prese il nome di Castel Sant'Angelo solo nel 590 d.C., dopo la leggendaria apparizione dell’Arcangelo Michele a papa san Gregorio Magno, nella quale gli annunciava la fine della spaventosa pestilenza che aveva decimato la popolazione.

Nel 270 d.C. l'imperatore Aureliano costruì le nuove mura per difendere Roma dagli attacchi sempre più frequenti dei barbari. Alla fine del Trecento papa Bonifacio IX fece scavare un fossato intorno al corpo di fabbrica circolare del Mausoleo, e murò l'ingresso originale aprendone uno più in alto, difeso da un ponte levatoio. In tal modo iniziò la sua trasformazione in quella fortezza inespugnabile che resisterà a infiniti assedi nel corso dei secoli.

Nel 401 d.C. gli imperatori Onorio ed Arcadio rinforzarono le mura Aureliane e le collegarono al Mausoleo, perché la sua forma a torrione e la sua altezza ne facevano un punto d'osservazione strategico. Divenne così il più importante caposaldo difensivo della città sulla sponda destra del Tevere, dal quale si controllava uno dei principali punti di accesso all'Urbe, il ponte Elio.

Nel 410 e poi nel 455 d.C. il Mausoleo resistette ai primi assedi dei Visigoti e dei Vandali, che non riuscirono ad espugnarlo ma saccheggiarono l’intera città. Poco dopo furono costruite le Mura Leonine per proteggere anche la Basilica di San Pietro.

Nel 537 d.C. Roma fu nuovamente attaccata dai Goti di Vitige, che cercarono di conquistare il Mausoleo scalando le sue mura con corde e scale. I romani si asserragliarono al suo interno sotto la guida del generale Belisario, il quale si rese conto che per difendersi non era possibile usare le balliste, perché non potevano scagliare i loro proiettili dall’alto verso il basso, ma solo di fronte.

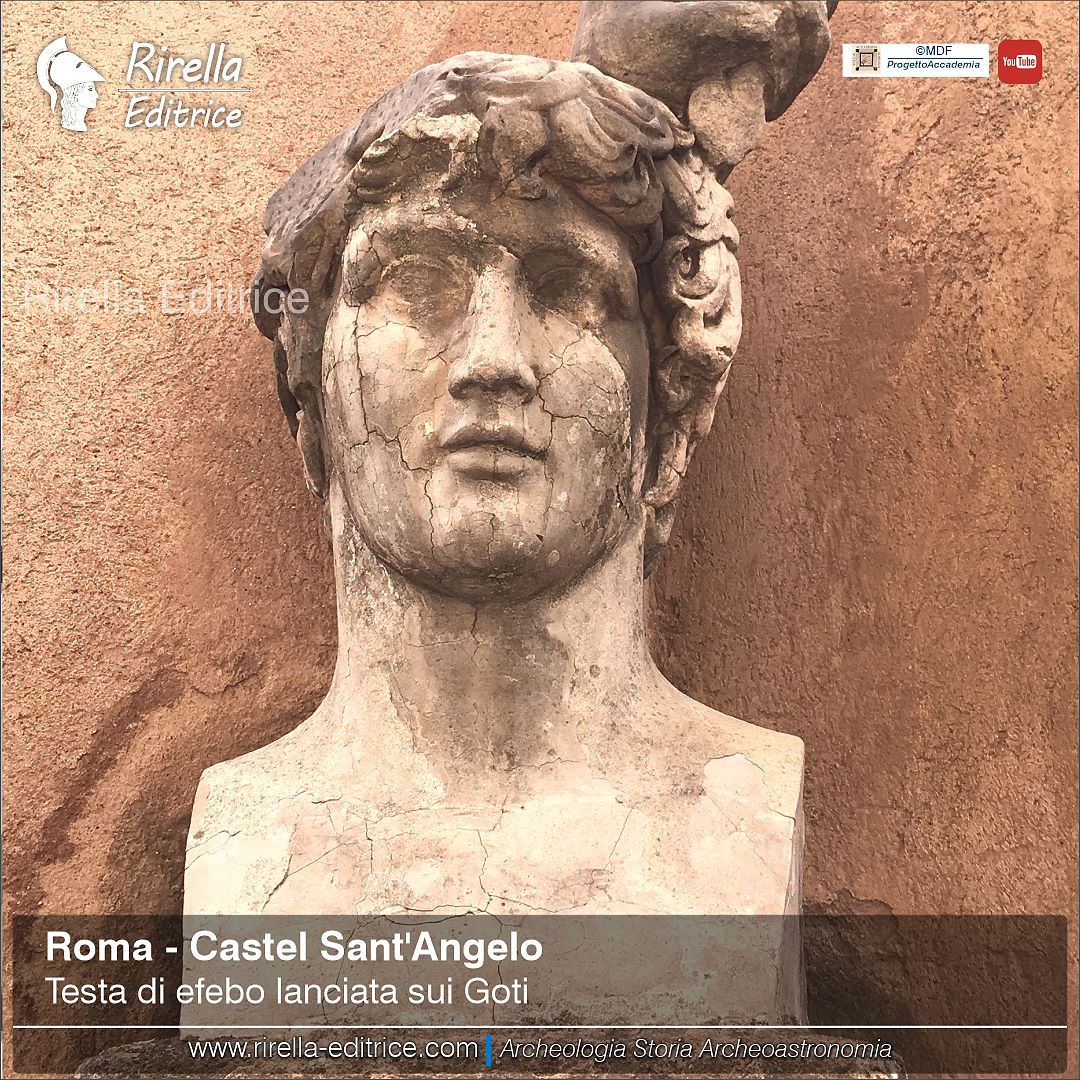

La situazione era disperata, ma a mali estremi estremi rimedi. Procopio di Cesarea, nel 550 d.C., pochi anni dopo, descrive l’assedio nel suo De Bello Gotico, e racconta che Belisario decise di fare a pezzi le statue antiche che decoravano il Mausoleo per adoperare i frammenti di marmo come proiettili, gettandoli sui nemici, che si diedero alla fuga.

Fu l'inizio della fine: quel momento in poi il Mausoleo venne depredato di tutti i suoi marmi preziosi; il travertino ad esempio fu venduto dal Comune e adoperato per pavimentare le piazze di Roma.

Alla fine del Quattrocento, quando papa Alessandro VI Borgia fece scavare nuovi fossati attorno a Castel Sant’Angelo, furono rinvenuti diversi rammenti di sculture, che confermano la veridicità del racconto di Procopio. Altri frammenti furono trovati a fine Ottocento, durante la costruzione degli argini del Lungotevere.

Nel 1527 vi fu il terribile assedio dei Lanzichenecchi, ma nemmeno loro riuscirono ad espugnare il Castello, dove il papa si era rifugiato assieme a qualche migliaio di persone, percorrendo il Passetto, un percorso pedonale sopraelevato che collegava la Basilica di San Pietro al Castello e fu usato come via di fuga in numerose altre occasioni.

Il saccheggio di Roma durò ben sette mesi, durante i quali i mercenari tedeschi bruciarono documenti, distrussero opere d'arte e massacrarono la popolazione con ogni sorta di violenza. E dopo mesi riuscirono finalmente a espugnare il Castello con la più classica ed efficace delle armi d'assedio: la fame. Finiti i viveri, papa Clemente VII fu costretto ad arrendersi.

Dopo di lui papa Paolo III dovette umiliarsi nel 1536 accogliendo come trionfatore Carlo V di Spagna in una città ridotta in miseria, approntando scenografie di cartapesta per darle una parvenza di dignità.

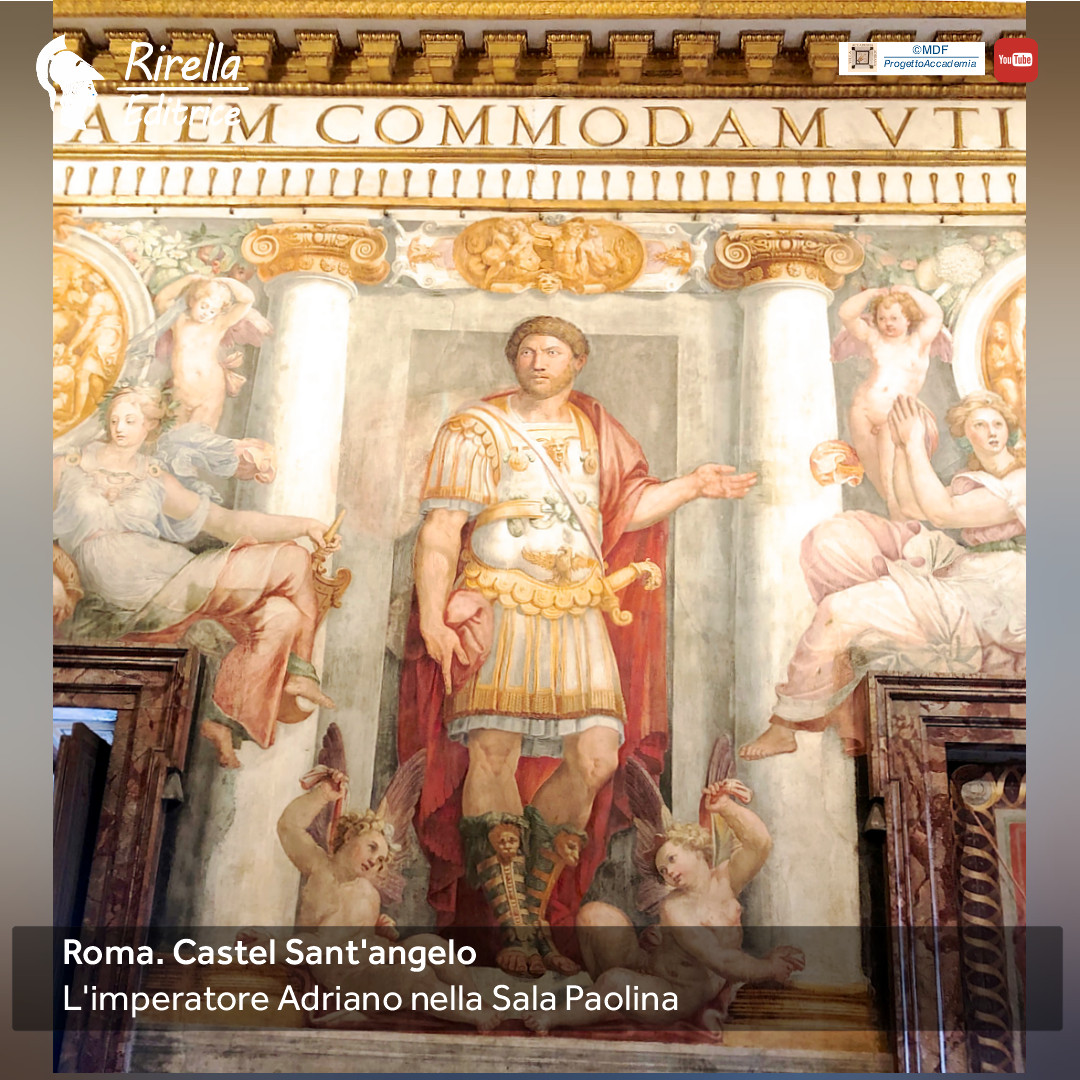

Nonostante queste tragiche vicende, dopo le devastazioni medievali il Castello rinacque a nuova vita perché a partire dal Quattrocento fu trasformato in residenza ufficiale dai grandi papi del Rinascimento e del Barocco.

Chiamarono alcuni dei più grandi artisti dell’epoca, fra i quali Raffaello, Michelangelo, Antonio da Sangallo, Baldassarre Peruzzi, per progettare e decorare gli appartamenti papali. Aggiunsero nuovi piani, logge ed ambienti e racchiusero i resti antichi all’interno di un meraviglioso guscio rinascimentale, che ne alterò profondamente l'aspetto.

Fu creato un accesso scenografico con un ponte levatoio, e papa Alessandro VI Borgia fece addirittura costruire dei giardini pensili con padiglioni affrescati da Pinturicchio ed un grande torrione per difendere il ponte.

La seconda vita di Castel Sant'Angelo è quindi strettamente legata alla storia dell'arte italiana e rinascimentale, che rispecchia la continuità del potere e dei suoi simboli fra l'Impero romano e la Chiesa, fra Adriano e l’Arcangelo Michele.

Questa e molte altre affascinanti vicende del periodo rinascimentale del Mausoleo diventato Castello vengono raccontate in dettaglio nel nostro libro «Castel Sant’Angelo. Mausoleo di Adriano. Architettura e Luce», che ne ripercorre la storia bimillenaria, strettamente legata a quella della città di Roma.

È un vera e propria guida per visitarlo con occhi nuovi, comprendendone il significato simbolico nascosto.

Il libro è in vendita nel Bookshop del Museo Nazionale di Castel Sant’Angelo, anche in lingua Inglese.